Table of contents

It started with a stone.

Not just any stone, but a “seeing stone” from Tolkien’s fantasy world, the kind that lets you watch anyone, anywhere, anytime. You don’t need to be in the same room. You don’t even need to be in the same timeline. You just... see.

Now imagine Peter Thiel. PayPal mafia, chess master, libertarian oracle, reading that, and thinking, what if we could build one?

In 2003, fresh off PayPal’s success, Thiel quietly incorporated a startup and named it after that mythical object: Palantir.

It was pitched as a noble cause. A software to help governments catch terrorists without violating civil liberties. A mission-driven company.

Investors laughed. One VC literally doodled through their pitch. Another told them their idea was a guaranteed failure. This wasn’t a pivot-to-crypto-then-AI type of startup. It was a moonshot from day one, backed by contrarian founders with zero interest in chasing trends.

Theil recruited Nathan Gettings from PayPal and two Stanford whiz kids, Joe Lonsdale and Stephen Cohen, to help build a prototype. Then he brought in his friend Alex Karp, a long-haired, philosophy-loving law school classmate with zero background in tech, as CEO.

Today, Palantir powers everything from U.S. Special Forces missions to COVID-19 vaccine rollouts. Its clients include governments, banks, health agencies, defense forces, and Fortune 500s.

The company nearly died in its first few years. Nobody wanted to fund it. Nobody understood it. Even Palantir’s own founders couldn’t fully explain what it was yet.

And the guy they picked to lead it?

He wasn’t a technologist. He didn’t code. He didn’t even like Silicon Valley. In fact, he openly loathed it.

But he had something else: a rare combination of philosophy, paranoia, and purpose.

This is the story of a company that most people have never seen, but almost certainly affects their lives: Palantir.

The Philosopher Who Hates Power (But Built a Tool for It)

Meet Alex Karp, a philosopher, law school graduate, and CEO of Palantir Technologies.

Not exactly your typical founder origin story.

Karp didn’t drop out of Stanford to code in his garage. He didn’t grind through YC or pitch decks or App Store updates. He spent his 20s buried in books about Hegel and Foucault. He earned a Ph.D. in neoclassical social theory from Goethe University in Frankfurt.

His doctoral thesis was about aggression and political identity. Not exactly lightweight startup material.

Thiel and Karp met years earlier as law students at Stanford. Thiel, PayPal’s co-founder, libertarian icon, and tech’s ultimate contrarian, was assembling a team to build something radical: software that could help intelligence agencies detect hidden threats, money laundering, and terrorist networks, without turning America into a surveillance state.

The goal was audacious: protect civil liberties and stop the bad guys. No easy feat.

Thiel had seen fraud detection at PayPal up close. Their system had to flag suspicious transactions in real-time, and the worst offenders weren’t hackers. They were smart. They knew how to game the system.

Terrorists, he reasoned, were no different. They’d slip through traditional surveillance. What the world needed was augmented intelligence: software that helped human analysts make sense of the noise.

He needed a CEO who could bridge worlds: tech and politics, idealism and realism, academia and espionage.

Karp was that guy.

He was skeptical of surveillance. He hated authoritarianism. He wasn’t even sure if he wanted the job. But in Thiel’s mind, that’s what made him perfect.

So in 2004, Thiel asked Karp to lead Palantir.

Karp said yes, and then promptly moved Palantir far away from Silicon Valley’s echo chamber. He set up HQ in Palo Alto, yes, but made it clear from day one: Palantir would never become just another tech company.

The company would grow not by chasing users, but by proving it could solve the world’s hardest problems, from counterterrorism to disaster response to cybersecurity.

They Were Told It Would Never Work

In its first years, Palantir struggled to survive.

Most VCs didn’t want to touch it. The idea of working with government agencies, let alone the intelligence community, was toxic in the startup world.

Sequoia’s chairman allegedly doodled through their pitch. Kleiner Perkins’ team gave them a lecture on why they were doomed to fail. The only people who believed were Peter Thiel and… the CIA.

Specifically, In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s venture capital arm. In 2004, they invested $2M to fund Palantir’s prototype. Thiel threw in $30M of his own.

Even then, they had no clients. Just a few engineers from PayPal, a handful of Stanford grads, and a wild idea.

They spent three years building.

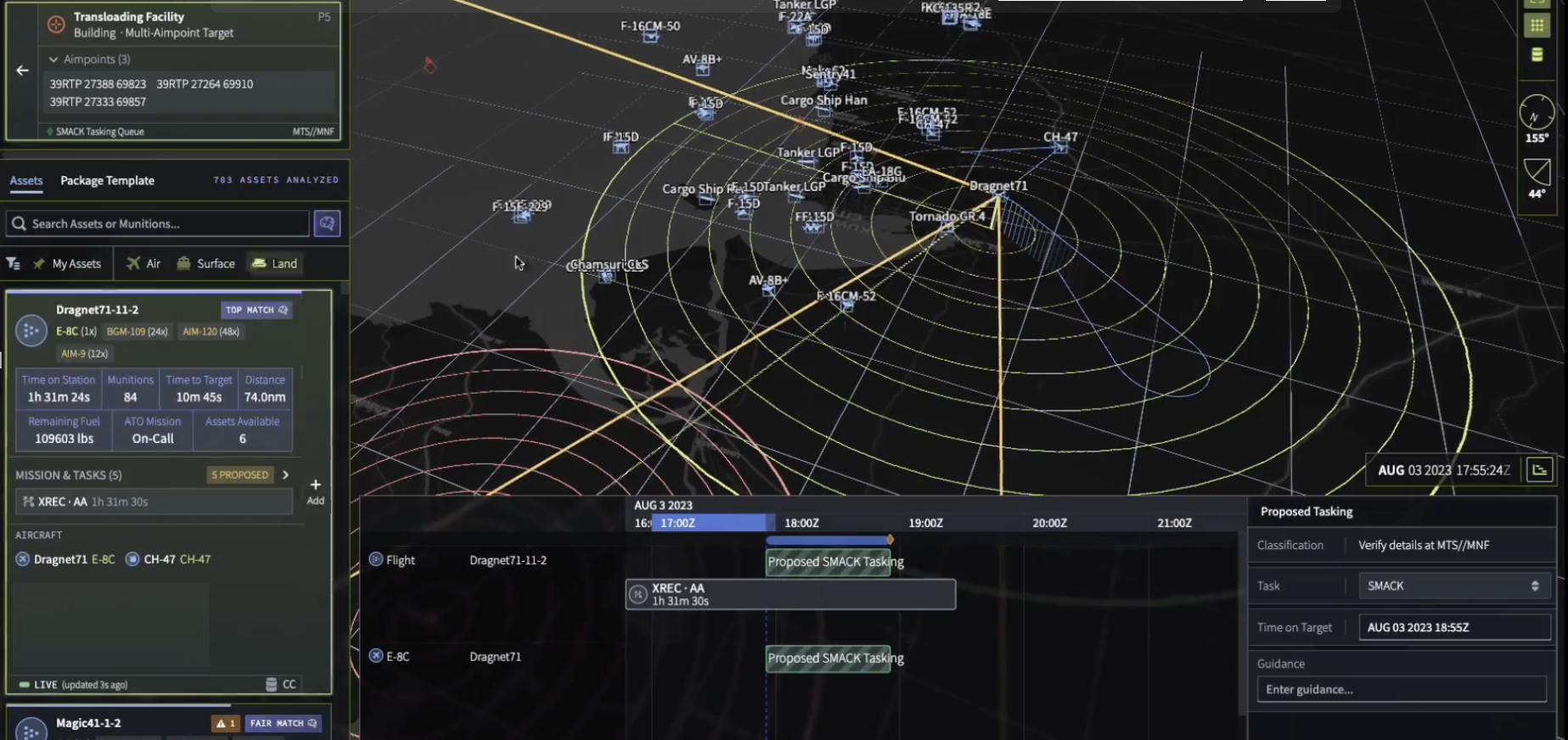

No revenue. No public hype. Just stealth pilots with intelligence analysts, cyber units, and military operatives. Instead of relying on artificial intelligence alone, Palantir focused on “intelligence augmentation,” software that made human decision-making faster, clearer, and more connected.

Eventually, it clicked.

Palantir’s platform could do what few others could: pull data from messy, siloed systems: emails, spreadsheets, satellites, bank records, and field reports, and visualize it in a way that made sense. That showed patterns. That could save lives.

Developing In War Rooms, Not Garages

It didn’t explode overnight.

Palantir’s rise was slow, painful, and eerily secretive, more like a military campaign than a startup blitz. It wasn’t blitzscaled. It was… battle-tested.

For the first six years, the company operated more like an intelligence cell than a tech startup. They didn’t hire marketers. They didn’t chase headlines. They sent engineers straight into war rooms, literally. Iraq. Afghanistan. Counterterrorism cells. Financial fraud teams. Field agents sat side by side with coders, hacking together solutions in real time.

This wasn’t SaaS. This was warware.

But warware doesn’t scale easily.

One Client At A Time and a Slow Pivot

By 2009, Palantir had landed its first major government clients. The U.S. Army. The NSA. The FBI. A quiet rumor started spreading through D.C.: “If your mission’s critical, get Palantir.”

They had traction. But not growth.

Karp refused to go the classic VC route. He avoided public demos. Turned down dozens of potential deals. Refused to take clients who didn’t align with their ethics. Even rejected contracts from China and Russia.

Palantir wasn’t just selling software. They were defining what kind of world their software would help build.

Meanwhile, Silicon Valley thought they were a joke.

Until 2010.

That’s when Palantir pivoted. Not its product, but its pitch.

Instead of selling directly to agencies, they created a deployment model. Embedded engineers. Real-time feedback loops. Software-as-a-service, yes, but with humans in the loop. Not just onboarding calls. Tactical support, operational planning, and mission design.

And money started pouring in.

First of Its Kind to $360B

From 2010 to 2015, Palantir’s valuation exploded, from a few hundred million to over $20B. They raised more than $2B in funding. Clients multiplied: the CDC, the SEC, the FDA, JPMorgan, Airbus, Credit Suisse, the NHS, and eventually… the Pentagon.

Still, they weren’t profitable. For years, they bled money. In 2018, losses hit $580 million. Critics called them bloated, inefficient, a glorified consulting firm with a UI.

But Karp didn’t blink. He doubled down on one belief: Palantir wasn’t here to grow fast. It was here to survive long enough to matter.

Then came 2020.

COVID-19 hit. Governments scrambled. Supply chains collapsed. Palantir stepped in with software already field-tested for crisis. They helped the U.S. and U.K. manage vaccine rollouts, track hospital beds, and monitor outbreaks. In weeks, Palantir became mission-critical infrastructure.

Revenue soared. In 2021, they hit $1.5B. By 2023, they were cash-flow positive for the first time. The company had 300+ clients across 40+ industries. Profit margins reached 30%. The stock price doubled. Institutional investors circled like hawks.

At the time of publishing this article, Palantir’s market capitalization (valuation based on share price and outstanding shares) stands at approximately US$364B.

Palantir is one of the most important, misunderstood, and quietly powerful software companies in the world. Not because it scaled fast, but because it scaled with conviction.

And the man behind it?

Still hates Silicon Valley. Still quotes Foucault. Still thinks about power the way most CEOs think about quarterly earnings.

Conclusion: An Unlikely Founder

Karp isn’t your optimistic and “charismatic” billionaire CEO archetype. He’s a skeptical academic with wild hair, broken German, a slight stutter, and a bone to pick with the entire system.

While everyone else builds companies that feel safe to pitch, Karp built one that took 10 years to understand. The last thing he did was to try to be predictable.

What can a founder learn from this?

First: The world does not need more consensus-driven builders who chase virality, mimic winning templates, and optimize for TechCrunch headlines.

It needs more people unafraid to go so deep into their curiosity that it alienates the room.

Second: If you think “being theoretical” makes you unfit to be a founder, you’ve bought into a lie.

Karp didn’t need to be a 10x engineer. His obsession with systems, power, ethics, war, and privacy gave him a lens most builders ignore. His training didn’t make him irrelevant to tech. It made him immune to its delusions.

Karp never blinked. He kept writing angry shareholder letters talking about moral philosophy, Nietzsche, and national defense like it was just another quarterly update.

The belief that only product-minded hustlers can change the world is convenient for investors, but it’s ahistorical.

Your quirks aren’t a barrier to your success. They’re the source of it.

The parts of you that feel too weird, too intellectual, too academic, too much. Those are the parts the world needs you to weaponize.

%20Logo.svg)

.webp)